Introduction

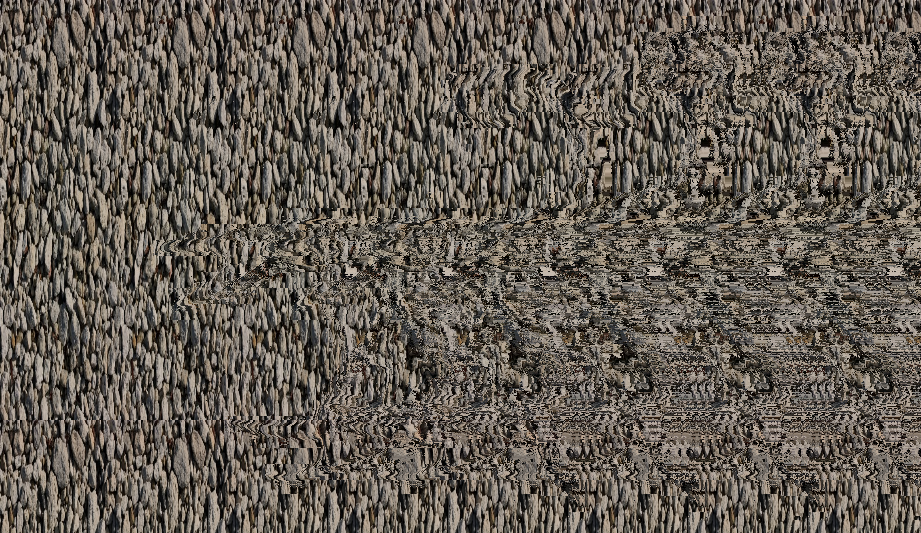

When you first encounter a stereogram, it might look like a chaotic pattern or a colorful blur. But with the right viewing technique, these images suddenly transform, revealing a hidden 3D world that seems to leap off the page. Stereograms have fascinated people for nearly two centuries, creating magical visual experiences without special equipment.

These optical illusions represent one of the most interesting intersections of art and science, using our natural binocular vision to create depth perception from flat images. From Victorian parlor entertainment to 1990s mall kiosks, stereograms have evolved dramatically while maintaining their ability to surprise and delight.

This article traces the journey of stereograms from their invention in the 1800s through their various transformations, up to today’s digital implementations.

1. The Birth of Stereoscopy (1800s – 1900s)

The story begins in 1838 when British scientist Sir Charles Wheatstone made a groundbreaking discovery. He realized that when each eye views a slightly different image, our brain combines them to create a perception of depth. To demonstrate this, he invented the stereoscope – a device that allowed people to view two slightly different drawings side by side, creating a three-dimensional illusion.

Wheatstone’s invention arrived at the perfect time, just as photography was being developed. By the 1850s, photographers were creating stereo pairs – two photographs taken a few inches apart to mimic the distance between human eyes. These early stereoscopic images typically showed landscapes, monuments, and scenes from distant places.

Victorian families were enchanted by this new form of entertainment. Looking through a stereoscope transported viewers to exotic locations like the pyramids of Egypt or the streets of Paris without leaving their living rooms. It was the virtual reality of its day, offering an immersive experience that flat photographs couldn’t match.

2. The Popularity of Stereoscopic Cards (Late 19th – Early 20th Century)

By the late 1800s, stereoscopic viewers had become common household items, and collecting stereoscopic cards (also called stereoviews) became a popular hobby. Companies like Underwood & Underwood and the London Stereoscopic Company mass-produced these cards, eventually creating libraries of tens of thousands of images.

The industrial revolution played a crucial role in this popularity boom. Advances in printing technology made stereoscopic cards more affordable, while improved transportation networks allowed for wider distribution. Stereoscopic photography became a global industry, with photographers traveling to remote corners of the world to capture new and exciting scenes.

Beyond entertainment, stereograms found important educational and scientific applications. Medical schools used stereoscopic images to teach anatomy, museums created stereo displays of artifacts, and geologists used them to study landscape formations. The immersive nature of stereoscopic viewing made complex information easier to understand and remember.

3. Stereoscopy in Film and Media (1920s – 1950s)

As motion pictures gained popularity, filmmakers naturally experimented with adding the third dimension. The 1920s saw the first commercial 3D film screenings, though the technology remained primitive. Viewers typically wore glasses with different colored filters (anaglyph 3D) to separate the images for each eye.

The real 3D movie boom came in the 1950s, partly as a response to the growing threat of television. Films like “Bwana Devil” (1952) and “House of Wax” (1953) drew audiences with the promise of objects seemingly flying off the screen. For a brief period, 3D movies were a major attraction, though technical difficulties and viewer discomfort eventually led to their decline.

During this same period, stereoscopic images found their way into advertising, comic books, and various forms of popular media. Brands recognized the novelty factor of 3D imagery and used it to make their advertisements stand out in increasingly crowded markets.

4. The Emergence of Autostereograms (1950s – 1990s)

The next major evolution came with the development of autostereograms – single images that create a 3D effect without requiring a special viewer. Early experiments with this concept occurred in the 1950s, but the breakthrough came in 1979 when Dr. Christopher Tyler developed the single-image random dot stereogram (SIRDS).

Unlike traditional stereograms that used two separate images, these new patterns contained the 3D information within a single image. By relaxing your eyes and looking “through” the image rather than at it, hidden 3D objects would emerge from what initially appeared to be just random dots or patterns.

The commercial potential of this technology exploded in the 1990s with the publication of Magic Eye books. These collections of colorful autostereograms became a global phenomenon. People everywhere could be seen staring intensely at seemingly abstract patterns, waiting for the moment when dolphins, dinosaurs, or other objects would suddenly appear in 3D. Magic Eye images appeared on posters, t-shirts, and even screensavers, becoming a defining cultural touchstone of the decade.

5. Digital Revolution and Stereograms (2000s – Present)

The advent of powerful personal computers transformed stereogram creation from a specialized art to something anyone could try. Software made it possible to convert 3D models directly into stereograms, opening up new possibilities for complexity and detail.

Digital technology also revitalized traditional stereoscopy. Modern 3D movies use sophisticated digital projection and lightweight polarized glasses, offering a more comfortable viewing experience than their predecessors. Virtual reality headsets create immersive stereoscopic environments by displaying slightly different images to each eye, much like Wheatstone’s original stereoscope.

Today, stereograms have found applications in various fields. They’re used in vision therapy to help treat conditions like amblyopia (lazy eye). Game developers incorporate stereoscopic elements into their designs. Artists create digital stereograms as a unique art form, sometimes combining them with animation or interactive elements.

Conclusion

From Victorian parlors to smartphone apps, stereograms have shown remarkable staying power across nearly two centuries. Their evolution reflects both technological advancement and our enduring fascination with visual illusions.

What began as a scientific demonstration has transformed repeatedly while maintaining its core appeal – the magical moment when a flat image suddenly reveals its hidden depths. As we look to the future, stereograms will likely continue to evolve with augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and whatever visual technologies emerge next.

The fundamental principles discovered by Wheatstone in 1838 remain relevant in today’s digital world, proving that good ideas, like good optical illusions, never really go out of style. As long as humans remain fascinated by the gap between what we see and what we perceive, stereograms will maintain their special place in our visual culture.

Insightful as always